Did Realist Artist Position Themselves Against the Academic Art

With art schools' integration into the university system, artists are required to present their work as written 'exegesis'. Here, Danny Butt traces exegesis dorsum to its origins equally a grade of knowledge production and considers its limiting outcome on fine art's own ability of revelation

At the end of the 18th century, Nazarene painter Eberhard Wachter rejected a position on the staff of the Stuttgart academy, noting that 'in that location is also much misery in art already; I do not desire to increase information technology.' i Wachter uttered his sullen epigram on fine art education well before the development of postgraduate programmes in studio fine art, but the weariness of his tone would take only increased if he had read the raft of 'written components' – normally in the form of an exegesis – that are now mandatory in art schoolhouse submissions. Examiners do their best to maintain fresh eyes in front of works that groan under pointless descriptions of dull making processes, overblown and unconvincing attempts by artists to write their own work in an art historical tradition, or perhaps worst of all, interesting practices (de)formed into 'research questions' that the works are then supposed to answer. Duchamp did his best to dissuade such thinking, believing that 'there is no solution, because there is no trouble.' 2 At present the demand to observe issues to satisfy a demand for academic rigour seems to be the problem.

These crimes of writing committed in art schools are not the fault of artists, who know all as well well that a written exegesis usually hinders great piece of work. Students oftentimes evade supervision of these enquiry reports – possibly hoping that the requirement might slip away unnoticed. Non because they can't write: visual artists can be formally gifted and inventive writers. But contemporary artists are reflexive critics of class in the nigh expanded sense, often unhappy with any institutional dictation of class or genre from to a higher place. Equally Dieter Lesage has argued, to require an creative person to prefer a item form of writing is precisely to fail to recognise their status as an artist. three Artists too seem to recognise that the university exegesis yields little aesthetic or professional person advantage: the market seeks the creative person as a producer of mystery, rather than an explainer. Ironically, the exegesis oft fails to record the student's learning through their reading, writing and talking nigh ideas and theory of various kinds, because this learning is precisely useful when it operates behind the scenes of an artistic work, rather than in forepart of it. In Foucauldian terms, fine art points to the emergence and refuse of stable discourses, zones where the seeable moves into or out of the realm of the sayable. If a concept tin be captured clearly in academic writing as a question, what would be the betoken of making fine art with it? The exegesis seems to go a peculiarly useless form both in the academy and in the art globe, existing merely to permit a bureaucratic calculation of the student's acceptability for an awarded degree.

In traditional theological do, the exegesis carried God's discussion to the world, a mission reflected in the term'south Greek etymology (ex - outward; hegeisthai - to lead or guide). God'due south terminal word could not exist directly accessed by humans, and then biblical lessons required estimation so they could be applied to everyday life. During the medieval birth of the academy, the scholastic methods of disputation and interpretation adult this analytical method of the critic, somewhen extending from the holy book to other works, including works of fine art. The small, fixed stock of artistic examples copied in the academy reflected God's design for the world, and these also required interpretive commentary to accomplish an imperfect broader society. Interpretation in the critical tradition relies on dialogue and argue – even today it is not customary for a contemporary artist to secure the estimation of their own work. Such attempts – increasingly demanded by research-minded institutions – not only seem a little naff, but also impose upon the liberty of appreciation that Kantian aestheticians have understood to exist at the centre of the art experience. This is not to say that the creative person lacks critical knowledge of their work, but theirs is merely the first in a chain of interpretations that run from artist, to curator, to audience and across. One time the piece of work reaches a public, the correct interpretation can no longer be the artist's holding if the audience is to discover their own feel of the work.

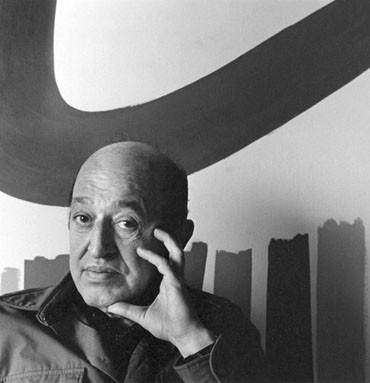

Prototype: Fine art critic Clement Greenberg

Science is the obvious culprit for the proprietisation and individualisation of estimation in the university art schoolhouse. In the modern universities from Berlin in 1810, science replaced theological scholasticism as the dominant European ways of stabilising the natural world for analysis and adding. Foucault described how the Renaissance era brought almost the conditions for the spread of scientific thinking, where relations between name and order; how to detect a classification that would exist a taxonomy became the preoccupation of the day four . Access to truth was democratised, or more correctly transposed from the institution of the church to the conservative gentleman. Today, we call up of scientific discipline every bit opposed to organized religion, but Robert Merton showed that the transition from scientia as noesis of God to scientia as cognition of nature was not a revolutionary shift. Instead, under the Protestant ethic, scientific experimentation developed as a method for the pious discovery of God'due south globe, while nature's religious underpinning moved from public to private language. five In the 19th century, for example, information technology was impossible for the boilerplate scientist to suggest that scientific noesis was incompatible with Christian thought. Natural philosophy was seen as a pious (if not religious) activity, proper for a gentleman precisely because it avoided the bitter arguments of scholasticism. Fugitive the interminable arguments about life and expiry, proficient and evil; the forward looking sciences bracketed such questions while pursuing always more highly specialised modes of investigation, whose resulting noesis of 'what is' would exist held with the 'practiced' individual.

As Haraway, Shapin and other historians of scientific discipline take shown, the written business relationship of experiments in the Republic of Letters became an exercise in the rhetoric of truth, which could be asserted by the author without the transcendental-theoretical problems of theological statement. six The scientific report would not be a set of instructions to be replicated or a set of arguments to be deconstructed, just a claim to significance by a 'pocket-sized witness', who must firmly position themselves in what Traweek calls a 'culture of no civilization.' 7 Lorraine Daston describes this civilization as reliant upon a moral economy of 'gentlemanly honor, Protestant introspection, [and] bourgeois punctiliousness.' 8 In this mode, the written report must be seen to 'guarantee' the validity and transferability of cognition equally a unit of truth. Ironically, this 'transferability' would be obtained through the suppression of both the written rhetorical skills of the creator and their tacit experimental cognition. Science would philosophically advisable writing every bit a supposedly neutral container for cognition in general. To achieve credibility the scientist must suppress the subjective conditions of production to construct a blank neutral facticity, guarding against the dread errors of 'idolatry, seduction, and project' that might compromise objectivity and breach decorum. 9

Of course, the 'errors' of excessive belief and fantastic projection are precisely the mechanisms through which the Romantic artist would come to brand their mark. Meanwhile, what Galison calls 'conditions of possible comportment' for the scientific researcher were emblematic of colonial patriarchy, with its well documented fears of the feminine body. ten In the 18th century, experimentalists became obsessed with development of 'spiritual and bodily regimens [that should] be rigorously followed to rein in… dangerous inclinations.' 11 Daston notes that the psychological and biophysical aspects of excessive belief were closely linked – the seductive lure of the imagination, in the eyes of the Cambridge philosopher More than, could exist avoided past steering clear of 'hot and heightening meats and drinks', past taking walks in the fresh air and by avoiding too much time in one's own company. 12 The scientific appropriation and regulation of the self takes on a moral season that is reflected today in science's hierarchical modes of industrial system.

The modern advanced'southward inventive and corrosive attacks on conservative morality were therefore not the kind of 'creativity' that led to their incorporation in to the enquiry university. Bernard Darras describes the art education of the final 2 centuries equally characterised by iv competing philosophies of development: i) the patrimonials, seeking to uphold the great academic traditions; ii) the functionalists, seeking social and economic evolution through cartoon; 3) the psychologists and educationalists, seeing fine art as a pathway to individual artistic and cognitive development; and finally iv) the avant-garde, reflecting romantic modernist principles of aesthetic autonomy. 13 Within the scientific academy, the psychology influenced educationalists accept generally had their hands closest to the rudder of curriculum, leading the evolution of 'creative doctorates' in U.s. colleges of education throughout the 20th century, adapted from the emergent models of the social sciences. While many North American commentators today seek to defend the MFA against the incursion of UK-style studio art PhDs, it was actually the US artistic doctorate that provided the model for the recoding of art as research in the UK universities during the 1980s and 1990s. These doctorates were supported in the mid-20th century past museum administrators such every bit MoMA'southward Alfred Barr, who saw simply positive things coming from the recognition of art as equivalent to scientific disciplines. The famous Usa educator Lester Longman, a notably bourgeois critic, wrote in 1946 that he wanted to develop

experimental work on a more advanced level so that we may contribute new ideas to the field of art as freely every bit New York or Paris… In the sciences information technology is generally expected that universities volition be in the vanguard of experimentation. I want to exist the start to exercise this in the field of fine art xiv .

Be careful what you lot wish for Lester! Instead of new laboratories to lead the arts, the incorporation of art into research degrees and science and technology policy funding has resulted in the hegemony of quasi-scientific modes of academic writing past art students. In this restricted vocabulary, artists are encouraged to stabilise their own work and explicate its contribution in a highly unproductive 'objective mode', reflecting the moral economies that accept been the target of and then many artistic movements. Artists are required to shut out the invitation to the critic, to secure the interpretation of their own work and justify its value. One is struck past the homologies with Foucault's account of the stakes of neoliberalism, 'the replacement every time of human œconomicus as partner of exchange with a homo œconomicus every bit entrepreneur of himself, being for himself his ain capital, being for himself his own producer, being for himself the source of [his] earnings.' 15 The life of the producer of their own value is a lonely one.

If art offers anything to the university – which should be kept as an open question – information technology is perhaps located in its critical culture that deconstructs the self-authoring productive subject. The critic as interpreter – with the artist themselves being the beginning to adopt the role – plays a key role in the the work'due south ethical character, where a work is understood to be more a container for the intellectual property of its author. Information technology is a heterogeneous social artefact that hovers ambivalently in the globe, constructed of what Spivak describes as 'figures, asking for dis-figuration' in the meeting between work and viewer. 16 This ambivalence brings into existence space for the critical community which tin can allow the work to work; the social globe where significance is debated and deliberated rather than protected past the individual and disseminated as an object. Any attempt to harness the criticality of the work in writing only paradoxically reduces its effectiveness as a piece of work.

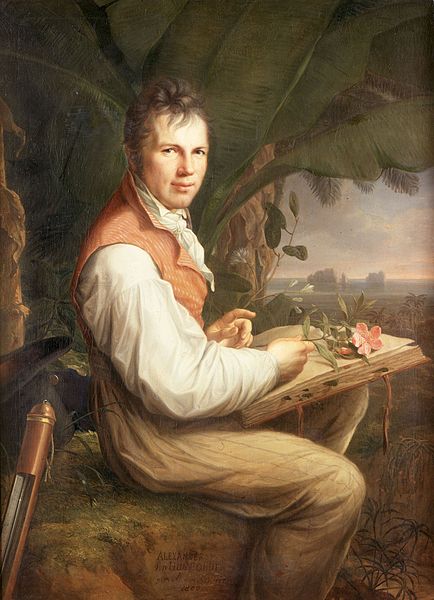

Image: Friedrich Georg Weitsch's portrait of Alexander von Humboldt, 1806

The research university has long been a property company for a raft of disciplines that fight for their own autonomous evolution. PhD regulations say very fiddling near how a student will undertake their research, considering every field or specialism has its ain way of doing things. Through historical circumstances at the birth of the PhD, the written thesis was the but technical class that could hold the triple functions of demonstrating the disciplinary knowledge gained by a educatee, disseminating it geographically and archiving information technology through time. 17 With the library no longer being the ideal form of archive or distribution, these written forms of the thesis every bit the sole container for knowledge are under pressure, fifty-fifty in the scientific disciplines, where diverse forms of 'knowledge transfer' are increasingly prevalent. In this context, it is hard to see how fine art'southward own disciplinary forcefulness will exist enhanced past adopting the quasi-scientific study over the characteristic forms of writing (or non-writing) that already operate in the visual art globe. Rather than simply adapting to 19th century models of scientific knowledge production, contemporary art could allow us to rethink material genres of cognition production and dissemination in the university. 18 Merely the but way this can occur is if the nigh valuable customary forms of practice in the visual arts are developed as the ground of the discipline'southward 'contribution to cognition', which will first and foremost be a critical analysis of knowledge's form. The vampiric form of the exegesis only suppresses fine art'south potential in the future academy.

Danny Butt <http://world wide web.dannybutt.net> has taught in art and design schools for xv years, currently at the Elam School of Fine Arts at the Academy of Auckland, New Zealand. He is office of the Local Fourth dimension collective and is currently working on a book on the fine art school in the research academy

Footnotes

1 Quoted in Nikolaus Pevsner, Academies of Art, Past and Present, New York: Da Capo, 1973 [1940], p.200.

two 'The Iconoclastic Opinions of One thousand. Marcel Duchamp Apropos Art in America', Current Opinion 59 (November 1915), pp.346-347. While I don't fully endorse Duchamp'due south renunciation of responsibility for bug, information technology is a statement that captures something key about the attitudes of the advanced. For a more than responsible only still usefully unscientific epigram on the status of art equally problem solving, I thank Ken Hay for pointing me to Frank Stella'south argument: 'There are two problems in painting: one is to notice out what a painting is and the other is to discover out how to make a painting.' In Robert Rosenblum, Frank Stella, Harmondsworth: Baltimore, 1971, p.57.

iii Dieter Lesage, 'On Supplementality', in Agonistic Academies, Jan Cools and Henk Slager (eds.), Brussels: Sint-Lukas Books, 2011. p.78. For a related argument on the motorcar-criticality of works using media theory, see Howard Slater, 'Post-Media Operators: 'Sovereign & Vague' Datacide seven (2000), http://datacide.c8.com/post-media-operators-'sovereign-vague'. The full general lack of fit between the fine arts and inquiry frameworks is discussed most extensively and entertainingly past Robert Nelson in his book The Jealousy of Ideas: Research Methods in the Creative Arts, London: Ellikon, 2009, http://bit.ly/yG6wlG

4 Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. London and New York: Routledge, 2003 [1970]. p208

five Robert Merton, 'Scientific discipline, Technology and Guild in Seventeenth Century England', Osiris no. four, 1938, pp.360-632. Encounter As well Steven Harris, 'Jesuit Scientific Activity in the Overseas Missions, 1540-1773', Isis 96, no. one, 2005, pp.71-79.

six See for example Donna Haraway, Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium.Femaleman_Meets_Oncomouse: Feminism and Technoscience, New York: Routledge, 1997; Steven Shapin, Understanding the Merton Thesis', Isis 79, no. four, 1988, pp.594-605; and Shapin, 'A Scholar and a Gentleman': The Problematic Identity of the Scientific Practitioner in Early Modern England', History of Science 29, no. 85, 1991, pp.279-327.

7 Sharon Traweek, Beamtimes and Lifetimes: The World of High Energy Physicists, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Academy Press, 1988. p.162.

8 Lorraine Daston, 'The Moral Economy of Scientific discipline', Osiris x, 1995, iii-24. p.24.

9 Lorraine Daston, 'Scientific Error and the Ethos of Belief', Social Research 72, no. ane, 2005, pp.1-28.

ten Peter Galison, 'Sentence against Objectivity', in Picturing Scientific discipline, Producing Fine art, Caroline A. Jones, Peter Galison & Amy Slaton (eds.), New York: Routledge, 1998, pp.327-359. Galison makes his most speculative and interesting argument along these lines in his essay 'Objectivity is Romantic', in The Humanities and the Sciences, Billy Frye (ed.), Philadelphia, PA: American Quango of Learned Societies, 1999, pp.15-43.

11 Daston, 'Scientific Error', op. cit., p.two.

12 Ibid.

thirteen Darras is commenting on Mary Ann Stankiewicz, 'Capitalizing Art Education: Mapping International Histories', in International Handbook of Enquiry in Arts Instruction, edited by Liora Bresler, 16,. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2007, pp.7-38.

xiv Quoted in Howard Singerman, Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999, p.208.

fifteen Michel Foucault, The Nascence of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège De France, 1978-79, Michel Senellart and Graham Burchell (trans.), New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. p.226.

16 Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, 'Ethics and Politics in Tagore, Coetzee, and Certain Scenes of Teaching', Diacritics 32, no. 3, 2002, 17-31. p21. Irit Rogoff helpfully points to 'singularisation' as the ethical potential of the critical attitude in the academy. Run across Rogoff, 'Practicing Enquiry / Singularising Knowledge', in Agonistic Academies (encounter n3), pp.69-74.

17 A seminar by Sally Jane Norman at the University of Auckland, 'Fine art - Inquiry - Values', 6th March 2012, extended my understanding of this point.

18 To my cognition this argument is beginning staged by Jacques Derrida in 'The University without Condition' in Without Excuse, Peggy Kamuf (trans.),Stanford: Stanford University Printing, 2002. pp.202-37. I give a detailed reading of this piece in the essay 'Neo-liberal and Futurity Universities', written for the We are the University zine, published to accompany Nationwide Twenty-four hour period of Educatee Action, University of Auckland, 26th September 2011, http://dannybutt.cyberspace/neo-liberal-and-future-univer...

Source: https://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/art-exegesis

0 Response to "Did Realist Artist Position Themselves Against the Academic Art"

Post a Comment